Some of Ruth Enke Chambers’ Memories

“Our hopes and fears do change their name as life goes on.”

From the preamble to J. L. Lejeune’s Annual Christmas Wishes to Withington Girls School 1925

[Ed Note: Another founder, Louisa Lejuene, wrote to the School’s Headmistress at Christmas 1925: ‘Our hopes do change their name as life goes on, and mine, my hope and wish for myself and those dear to me, is that courage and love and the power to pluck little joys from the wayside may last – and even grow – to the end of the pilgrimage, which I hope is the beginning.’ See http://www.withington.manchester.sch.uk/about-school/page/founders-withington-girls-school]

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Foreword

by Derek Chambers

As I approach fifty I become increasingly conscious of the passage of time and its consequences: aches, pains, and deteriorating eyesight on the negative side, but, on the positive side, the ever-growing numbers of people who are connected to me by a family relationship. As children are born, grow up, marry, and have their own children, our family connections spread like the ripples in a pond that follows a pebble’s plop. But as those ripples undulate outwards, their origin often smooths and disappears; and so it is with human beings, families and their remembered records.

Human beings form a great multitude, a crowded caravan traveling together through trackless country on a journey whose origins and whose destination are equally unknown. We are born, live, and die accompanied by some who are there when we arrive but leave before we do, and joined in our journey by newcomers whom, when we depart, we leave to travel on. As life passes, the crowd around us shifts and mixes, bringing new faces into our ken while others are carried off by the topography of circumstances to fade into the distance.

At first we are not greatly concerned with our place in the caravan, although we may pass through a stage in early youth in which we toy philosophically with the Meaning of Existence, Why Are We Here, and other capitalized questions. But, as our attention is deflected to the more prosaic task of making our way in the world, we put such speculations aside, though only into abeyance it seems since they come surging back in mid-life as we come to realize that there really is only one life and that the paths we take at each crossroad of choice definitely do preclude ever taking the other route.

And so we are brought once more to speculate about our particular, personal place in the puzzle of existence, our appointed position in the caravan. Our biological roots, our genetic inheritance, and the fact that ancestors of ours lived and died in what are now dim historical times, all work to awaken an interest in our origins. So it was for me.

However, I also came to realize that, although my mother had told me many stories about our family, because I was not gripped with interest at the time I had forgotten many of the facts; the ripples of the pond were there to study but I had not the eyes to see. And now, conscious that my mother is mortal and aging, and that once she has gone so will go an important, encyclopedic source of first hand information and keen observation gathered over the decades, as will also go her skill of making the bare facts about people come alive, revealing the human qualities behind them, I have encouraged Mum to write about her life, the people that she knew, the places that she visited, and the details about her ancestors that she had come to know. She has responded with what follows, tracing her life from its earliest beginnings on Galiano Island in 1910, up to mid 1989. Woven into this narrative are bits and pieces about others, members of the family and not, who played a part in shaping her memories.

Interspersed in the text are photographs illustrative of its people, places or subjects. Choosing which photographs to use was extremely difficult as there is such a wealth. In the end, rather than including a family pantheon of important looking Enke men and women, brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, I have restricted the choice to those who occupy a significant place in Mum’s narrative. Perhaps there will be a future opportunity to widely reproduce the remaining family pictures.

In addition to Mum’s story, I have taken an editor’s prerogative and incorporated, where relevant, other material which has come to hand. This includes some brief notes about Alexander MacLaren (my matrilineal Great-Great-Grandfather); the text of an article written for The Horn Book Magazine by Marion Enke (my maternal Grandmother); extensive notes prepared by my maternal Grandfather, Max Enke, describing his experiences during World War II; and some notes on my maternal great-great-great-grandfather, Adam François Lejeune. These latter three comprise respectively Appendices A, B and C.

The task of typing in the nearly 55,000 words that are contained here has been a long one, but one marked with fascinating periods of complete immersion in life decades in the past, as I was transported to another time and place. Not uncommonly, after some days of working at the material I have reluctantly surfaced, as if waking from a dream, to be surprised by the present and its often uncomfortable realities. However, again and again, I have then seen my grandchildren and been once more reminded of the quickness of life and the wonderfulness of all children. It is for them that I have done this.

Narnia, Knutsford

October 30, 1990

********************************

January 2011

It is more than 20 years since I wrote the words above and now I am approaching 70. Much has changed in the meanwhile. Mum died on January 11, 2002. Madrona Farm was sold in 2010 to TLC. And technology has advanced to the point where inserting images into documents is very simple. So, I am revisiting Mum’s autobiography to actually insert the images that I talked about above.

But I am also taking advantage of the digital advances of recent years. This document, when finished, will be available as a pdf download, but will also be published in a blog, thus making it considerably more accessible.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Table of Contents

Purpose

The Early Years (1910 – 1919)

Oaklands (1919 – 1921)

Manchester and Withington (1919 – 1921)

The Aunts and Uncles

Edward

Victoria (1921 – 1924)

Alexander Maclaren

England and the Continent (1924 – 1931)

Boarding School

Pinehurst and Oaklands

Austria

Oxford

Belgium, 1930

Trekweg

California, 1931 – 32

Easter, 1932 – December 31, 1937

1938 – 1939

1940 – 1942

1942 – 1949

1950 – 1951

1952 – 1982

Babies Bonfire

Nature Conservation

Stephen

1982 – 1988

Purpose

Dear Family – Present and Future Unknown

I want to describe some of the people and places that had a part in making me what I am.

Mine has not been a distinguished life by any means. Yet, for me, its been most interesting and mainly enjoyable. But a fascinating part of family life is that one never knows which child or grandchild will, as an adult, wonder about former relatives, how, when and where they lived. And when these individuals reach their 50s they may know 5 generations of one family. I did. At 53 I’d met grandparents, parents, my own generation, my children, and even my first grandchildren in the shape of twin boys born in July 1963.

Sometimes it’s intriguing to see some remembered feature or characteristic reappear. A way of walking, the shape of an ear, a tone of voice, a swiftly changing mood. Such small details, and yet, in an instant they evoke memories of another decade, a different place, a faraway but half-forgotten world.

Ruth Enke Chambers

Victoria, B.C.

July, 1988

The Early Years (1910 – 1919)

I was born in the upstairs bedroom of a farmhouse in the valley at the south end of Galiano Island. It was a wet December night, the 5th, in 1910, and the rain was coming down in long swishes. So wrote my darling Grannie Lejeune who had come from Manchester to Galiano for the birth of her very first Grandchild. Her letter, dated December 6, was to her son Russell who had emigrated to Western Australia (and who was later to die tragically, shot dead accidentally by a bullet from a kangaroo hunter’s rifle ricocheting off the rib of one of his prey), and was mainly to tell him that the baby had arrived the night before, and was a little girl to be called Ruth. It was sent to me by Josceline Lejeune who was Grannie’s first Australian grandchild. So now it’s in a farmhouse in a valley at the south end of Vancouver Island.

Mother was unwell for weeks after the difficult birth. Life on the island was different with a baby to consider. Picnics, outings, visitors were no longer a pleasure. Just extra work. She took the baby to Europe to show to both sides of the family. Max, realising she was an urban not a rural type, enquired about Victoria’s architects. Keith, who designed Christ Church Cathedral, got the contract. (Xeroxes of the plans for the Island Road house are in the Provincial Archives.)

By 1913 we were living in a large house, at 572 Island Road, on a hill in Oak Bay, an area that is now part of Greater Victoria. The house is still a familiar landmark with its black and white timbers, great size and its peculiar lookout room that rises like a bump from the main ridge of the roof. That room was reached by a ladder from the attic landing. Its strangeness and its many windows fueled and increased the German spy stories in World War I.

War hysteria is not new and has taken many forms over the centuries. It ran high in Oak Bay. Max Enke was certainly not an Anglo Saxon name, they said. A man with a German sounding name building a big expensive home that had a clear view southwards of all the ships on their way to Vancouver. If you watched carefully, the rumours ran, you could see figures in the windows silhouetted by the flashing beams of the Trial Island light. The figures moved and you could be sure they were speaking German. They were watching for a submarine to signal them from the strait. Why else would Max Enke keep a good clinker built rowboat on Shoal Bay beach? Rowing out under cover of darkness. Spies — dangerous German spies — no doubt about it at all. And children at kindergarten were told by their parents not to play with Ruth as her Daddy was a German spy.

Such tales seem unbelievable now. But so do accounts of the Lusitania riot in Victoria in 1915. On May 7, 1915, the Cunard liner Lusitania was torpedoed off the Irish coast on her way to Liverpool. She sank with great loss of life. The news of over 1000 passengers lost, reached Victoria the next day. The May 8 issue of the Victoria Daily Colonist had editorials on the sinking and on that weekend of May 8 and 9 a real riot began with the wrecking of the Blanshard Hotel which had been the Kaiserhof. An excited crowd was breaking glasses in the bar and throwing furniture into the street. Soldiers were summoned from their barracks at the Willows — off duty police were called in. The swelling crowd outnumbered soldiers and police. The mob set out for stores whose owners had German sounding names. There was looting of groceries, tobacco and drygoods, and Mayor Stewart read the Riot Act. The May 8 – 14 issues of the Daily Colonist make strange reading in 1988.

I enjoyed the years at 572 Island Road. Except for a 1919 – 1921 trip to England and Belgium, I was at 572 until I was taken to England in 1924 to go to a boarding school in Sussex.

In that early part of 572, I’d be the age when it was fun to build tree forts, run free on the hill, and shoot wildly with a bow and arrows I’d been given. The hill was truly a fine place for children to grow up in. Open grassy places to run through, paths between the broom bushes, hiding places among the windblown stunted Garry oaks that lay against the southern slopes of the hill. Each year in June there was a thrilling morning of the very lowest tide when one could reach certain rock pools and see places that were unattainable the rest of the year. In one deep crevice there was something living that looked like a butcher’s slab of liver in his store.

The flowers on the hill were mainly what I knew later as the Garry Oak Arbutus association. There were white erythroniums, too, usually growing under the oaks, Indian paintbrush, larkspur, camass. In the 1980’s “the hill” is an Oak Bay municipal park. It became a park just weeks after I’d scattered Stephen’s ashes in a grassy stretch within sight of the windows of the room where he was born in 1916.

It was on the hill, too, that I had my first glimpse of Geologic time. My father and I had walked to the rocky ridge at the eastern end of the grassy part of the hill. There we sat, looking at the view and a house below. My father said a great river of ice had passed over these rocks millions of years ago. The force of the moving ice had gouged out valleys and rounded hills that were not as high as the ice was thick – and in places a boulder imbedded in the ice scratched and grooved the rocks. He showed me a groove on the rock where I sat and gently guided my forefinger along that groove.

Now in 1988, about 15 paces from my back door, is a patch of bare, glaciated,, striated rock.

I like the look of it.

Oaklands (1919 – 1921)

In 1919 my father wanted to see how his father and sisters had survived the German Occupation of World War I. During the war we’d had no news – and, since the Armistice we’d had some but my father wanted to see family and battle fields for himself.

The family factory, that imported rabbit skins, processed them, and turned them into fur felt for the hat trade was at Eecloo, a small manufacturing town midway between Bruges and Ghent.

The liner we sailed on had the usual passenger list with names printed alphabetically. There we were “Mr and Mrs Max Enke, Miss Ruth Enke, Master Stephen Enke.” One morning, a woman walking on the deck, stopped me and asked “Are you the little Enke girl?” I nodded. “People with a name like that shouldn’t be allowed to travel,” she snapped.

At the time I was puzzled. However, before we returned two years later, I’d seen the World War I battlefields in Flanders, ruined Ypres and gained some knowledge of the carnage of the war. Slowly, slowly, from places visited, and from books read, I began to understand a little about the damage war could do to minds as well as bodies.

We found that my grandfather had survived the war intact but a bomb had landed on the big front lawn and shattered windows in the front of the house. The big bay window in the dining room was boarded up, and we had the electric light on for all meals.

| Oaklands, the home of Hermann Enke, father of Max, and of Max’s twin sisters Adeline and Paula Enke |

On the morning after we arrived, my cousin Margaret, who was 3½ years older than I and lived next door at Pinehurst, came over to meet us all and show me around.

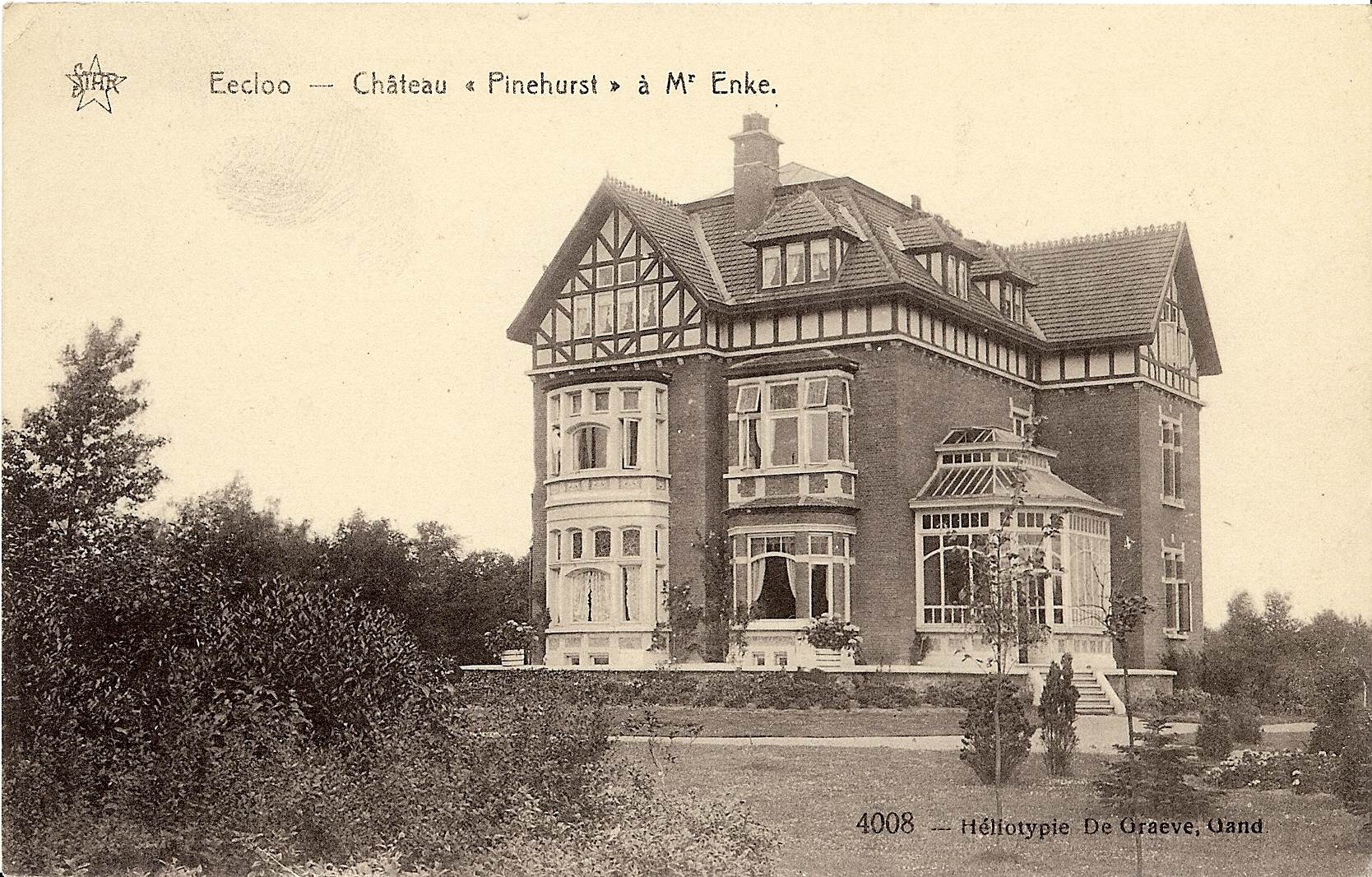

| Pinehurst, the home of Peter and Isabel Armstrong |

She suggested going to the Pill box. I was mystified as we went along the sandy path between espaliered pear trees. For Margaret said that the Oaklands pill box was in the back field and camouflaged so it couldn’t be seen from the air. When we reached the far end of the field, Margy (as her family called her) pointed to a low cement boxlike affair that was covered with sods of grass. In the winter it flooded down below, Margaret said. They had a pill box in their birch wood Margaret said. The trees hid it partly from the air, and birch branches had been spread over it like a concealing mat.

In the next few weeks Margy and I often cycled along the road that led to the village of Lembeke. We saw several other pill boxes in the wayside fields. Years later my father explained about this curving line of carefully concealed gun positions.

One morning Margy and I were told that we and my parents were going to Ypres next day. Just a day trip in the big Enke car, and the chauffeur Kamiel would drive. We’d be seeing world history with our own eyes, my father said, and we’d remember it all our lives. We didn’t want to go. But we went. Two cross kids. We stopped at one or two spots on that route through the flat treeless land. At one such spot we walked along a designated track that wound among the shell craters. At another we walked along a short stretch of muddy trench. For many years I had a snapshot of Margy and myself standing on top of a wrecked tank. Our hair was blowing in the wind and I was wearing an ugly but extra warm winter coat.

I went to Ypres several times after that first visit with my parents. For in the late 1920’s, when I was at boarding school in Sussex and my parents were in Canada, my official guardians were Margy’s parents, Peter and Isabel Armstrong, who lived at Pinehurst, the house next door to Oaklands. [Ed Note: Peter Armstrong, Max’s eldest brother, was christened Hermann Peter Enke when he was born in 1876. He later married Isabel Lunt whose mother’s maiden name was Armstrong. During World War I, because of the virulent anti-German feeling in England, Hermann changed his name to Henry Peter Armstrong.]

Ypres was not a long drive from Eecloo and it was interesting to see the gradual changes. The fields we drove past were no longer a dreary battlefield pocked with shell craters. They’d become farm fields, though all trees were comparatively young. Ypres was ready for tourists and shops sold books of sepia-coloured picture postcards — showing Ypres before the war and after — cafe’s, patisseries, restaurants, hotels. But the big reminder of the war was the white marble Menin Gate where the names of the missing men were printed in gold on the white panels of the gate. There were interior stairs you could mount and always, at each side, were the golden names on white. These were the missing men, not even found, just blown to bits, bodies squashed into the blood-soaked mud of what had been fertile farms. A foot left in an army boot, an arm here, a leg there. No wonder the later poets of World War I wrote so bitterly as the slaughter dragged on.

Some Eecloo stores had picture postcards of the town and nearby features. The card of “Oaklands” was labelled Château Enke. According to Larousse Château is simply “a fine big country house.” It was certainly large, and originally it was in the country for the Oostveldtstraet (Eastfieldstreet) ran between fields and farms and was the direct way from Eecloo to the village of Lembeke.

[As an aside — the parents of Remi de Roo, Bishop of Victoria, emigrated from Lembeke to Canada where Remi was born. His father died in Manitoba.]

* * *

The Oaklands drawing room and dining room had the highest ceilings of any house I’d ever seen.

The drawing room was divided by an archway with, on either side, a swoop of brown velvet curtain fringed with bobbles. Normally the curtains were looped back by golden cords with fancy tassels.

In the front drawing room was the oil portrait of Hermann Enke that, left to my brother Stephen, was lost in the fire that destroyed the house in Santa Barbara.

The back drawing room became magical at Christmas. The gardeners used to bring in a tree so tall that it almost reached the high ceiling. The butt of the tree was set in a strong metal holder that was part of an unforgettable music box. The Christmas tree ornaments were brought down from the attic. The sturdy tins holding the ornaments were those 9x9x9 tins in which Peak Frean, and other such firms shipped their biscuits to wholesalers. The tree was lit by candles and revolved slowly as the music played. By tradition the tree stood in the bay window of the back drawing room, the candlelight was soft, the familiar ornaments appeared year after year. At the time I never wondered why there were only two of the slotted metal disks (rather like the perforations on rolls for a player piano. Just the same method, I guess.) Two disks, so we had just two tunes. I did not care for the Last Rose of Summer but Marching Through Georgia was fun.

Decorating the tree was a task for Margy and myself. It took us three days. Always when the candles were lighted an adult stood casually by the bay window. A hollow metal curtain rod was ready to use as a blow pipe if a candle should gutter or burn too low.

There were two special evenings in the Christmas season. On one all the children of the garden staff came. The other evening was for the children from the row of houses just across the Oostveldtstraet. On the tree was a special present for each child who came forward to get it as the name was called. After that there was a short interval when some of the mothers urged a child to recite a verse or sing a song. We listened attentively, clapped loyally. The finale was my grandfather standing in the doorway, and slipping a silver coin into the each child’s hand as part of the handshake. I think there may have been cookies or coffee in the kitchen with Lena and Marie. (In 1921 most of those Christmas guests wore sabots. These were left in the back kitchen as they had sort of carpet slippers worn inside sabots.)

At the time these occasions seemed lovely to me. Since then I’ve often wondered how those parents felt in their hearts. It seems too feudal to me now.

Manchester and Withington (1919 – 1921)

The 1919 – 1921 trip to Europe was part Belgium and part the Manchester suburb of Withington where my maternal grandmother lived at 8 Burlington Road.

It was raining the afternoon we arrived in a horse-drawn omnibus as we had too much luggage for a taxi. My grandmother ran out to greet us and she and mother began to exchange news. I ran into the garden where a leafless tree looked easy to climb. In minutes my hands were black with soot, and my neat beige travelling coat was ruined, or so my mother said. Thus I learned that trees were not for climbing in Manchester.

The garden beside the house was a stretch of long roughish grass that had been a tennis lawn. At the back of the house was a neater lawn outside the windows of the South Room, a room I’ll remember as long as mind and memory last. Less grand than a formal drawing room, more than a sitting room, it had a glass-fronted bookcase in the corner. The top shelf of this was “the Museum” holding unfamiliar shells we mistakenly called Maori shells instead of cowries that are found in the warm seas in Asia and the extreme south of India. These glossy shells were used as money in parts of Africa we were told. So we used them as money when we played gambling games.

The great pleasure for me was the shelf of books in the bedroom. They belonged to my youngest Aunt, Caroline, who was born after her father’s death in 1899 [Ed. Note: this is not correct. Caroline was born in 1897]. I’d had a few books in Victoria, but nothing like this. Several of the Colour Books by Andrew Lang were there. His Blue Fairy Book (1899) and the first of his collection to appear; there was the Green , the Olive and I think two others. I read them avidly, not so much for the fairy content, I think, as for the smooth and flowing style. Howard Pyle was there too. I turned again and again to his Merry Adventures of Robin Hood. That shelf of books was a special part of the European visit.

The South Room was special too. Grannie’s little slipper chair was a novelty to me. In its South Room days it was covered with red velvet. In the 1980’s that same chair was in a Pasadena living room where chair cover and curtains were of the same light coloured patterned material.

When the Manchester Guardian’s great editor C. P. Scott bicycled over from his home in Fallowfield, he and Grannie would sit talking in the South Room, and I wish now that I had been older because often they were discussing the newspaper ideas and policy. But I was too young to realize what a noble and important man he was. I just thought of him as “Scottie” who put his bicycle on the front porch if he rode over on a rainy day. His daughter married C. E. Montague who wrote the novel Rough Justice.

While we stayed at 8 Burlington Road on that 1919 – 1921 trip, I went to Withington Girls School of which Grannie had been one of the founders.

I’m still grateful for my spell at that school, the best school I would attend. Many of the students were the daughters of Manchester’s intelligentsia, and thus many were Jewish. They did not come down to the daily assembly, and they were absent from school on certain Jewish festivals. Such differences were unimportant, and were taken for granted. There was no trace of anti-semitism, and mercifully none of us could foresee the coming of Hitler. Even now, the sort of laughing comment about Jews fills me with cold contempt for a mind that lacks charity.

The two individuals I remember best from Withington Girls School are Doris and Miss Casswell.

Doris, small, palefaced, red-haired, was on a scholarship. Good at most subjects, she excelled at Math. A broad, broad Lancashire accent. But her mind snapped tight on a Math problem.

Miss Casswell admired the natural world in the true sense of admire. For the Latin verb mirare means to admire or marvel at. She could make us marvel, too. The morning I remember best was about Paws and Claws. Miss Casswell drew two simple diagrams on the board. One was of a dog’s foreleg and paw. The second was of a cat’s leg. We saw the muscle in the cat’s leg and how the claws retracted. Then we contrasted and compared the two diagrams. Somehow, to this day, a purring cat, kneading its paws, a dog’s claws clattering a little on the linoleum, can remind me of Miss Casswell and that long ago lesson in Withington.

The Aunts and Uncles

The 1919-1921 trip was the first real encounter with our relatives for Stephen and me. I’d been exhibited as a baby to the Enkes and Lejeunes. But Stephen, born in 1916, was only known to them through Mother’s letters and his father’s snapshots. There seemed to be swarms of Lejeunes and only three Enke’s of my parents’ generation and “Papa” who was Hermann Enke who lived until 1926.

Grannie Lejeune, who married Edward before she was 20, had Franziska in 1878, followed by 3 girls, 3 boys, 4 miscarriages according to accurate Max, and, finally Caroline born posthumously [Ed. Note. This is incorrect. Caroline was born in 1897] as her father had died in Zurich in 1899 while he was travelling in Switzerland with his second daughter, my mother, Marion.

I’ve never seen a formal group photograph of all 8 children. The Isle of Man photograph, of which Max made a copy, included Arnold but not Caroline. The formal photograph, nicknamed The Oliver Cromwell Hats belonged to Juliet for years. There should be a copy of it in the family photograph box currently at Narnia. Four solemn little girls, Franziska (1878), Marion (1879), Juliet (1880), and Helena (1881 or 1882). All wore tall black velour hats like those worn by the Roundheads in the seventeenth century Civil War between Roundheads and Royalists. There were two distinct physical types among the 8 children. Marion, Juliet, Arnold and Caroline resembled their father and had his blue eyes and light brown hair. Franziska, Helena, Alick and Russell had their mother’s brown eyes and slightly darker brown hair.

The girls were more academic than the boys. Franziska went up to Oxford, read English, got a first class. Marion, considered good at Math in her school days went to Cambridge (Newnham College) as Cambridge was then considered better than Oxford for Math. Released from the responsibility of being a prefect, and the oldest but one of a large family, Marion decided to enjoy her first year at university. She played a lot of grass hockey, went to endless cocoa parties and ended her year with a 40% examination mark. This was not good enough for the authorities. She must either switch to another subject or leave and make way for a more dedicated student. She switched to English, completed her course and gained a first class.

Juliet, the third Lejeune girl did not go to university, I think. She had some teacher training and got a certificate or diploma that would have enabled her to teach small children. Helena, who like Juliet never married, went to Oxford, read English and got second class marks.

Franziska and Marion both married and neither made professional use of their education, although Marion did teach for a year at a new school for girls at Southwold on England’s East Coast. There she met a teacher, Lucretia Cameron who later had a school for girls at Seaford in Sussex [The Downs School, Sutton Road, Seaford]. Although Helena only got a second class and was considered academically a mite inferior to Franziska and Marion, she had a teaching job at Huyton near Liverpool. This Huyton school for girls had, I understood, a good scholastic reputation. When I was Oxford in the late 1920’s, I met a girl from Huyton. She was a tall, blond, almost classic beauty with a broad Lancashire accent and a scholar’s gown. Her name was Josephine, but I’ve forgotten her surname. She was at Oxford reading English, she said, because of a wonderful teacher she’d had – a Miss Helena Lejeune. She described the inspired teaching, the extra coaching time given so generously and enthusiastically. She couldn’t have afforded university without a scholarship, she said, and winning it was entirely due to Miss Lejeune’s teaching.

Caroline went to Manchester University, read English and emerged with distinction. She never taught. Instead she worked for the Manchester Guardian (later called the Guardian), becoming their film critic. She was convinced that the cinema was a new twentieth century art form, and pointed out to the paper that as films were released in London before Manchester, the paper would be better served by having her as film critic in London.

After Tony’s birth in 1930 and Caroline’s switch to the Observer, her column of film criticism was called At the Films. She was still writing in the 1950’s. I’m unsure of when she retired. That column was very well known, and she was at her best in the 1940’s I’d think.

Caroline’s books were Cinema, Chestnuts in Her Lap, and her autobiography Thanks for Having Me.

Arnold wrote textbooks about the English language. He had no university education but he had a lively and enquiring mind. And he was of that rare breed – a born teacher. Emigrating to California in 1924, he spent several years at the Thatcher School in Ojai. There he met Archibald Hart and much admired his book Twelve Ways to Build a Vocabulary. Together, and at Dr Hart’s request, they wrote The Growing Vocabulary. After the Thatcher School, Arnold joined the Crane Country Day School in Santa Barbara and, later, became its headmaster. He wrote The Latin Key to Better English. He died before PBS gave TV audiences The Story of English. It would, I’m sure, have been much appreciated by Arnold.

Edward

So many Lejeune men have had Edward as one of their given names.

A list of Enke/Lejeune names was among Max Enke’s papers. Max, a stickler for accuracy, had listed

1) Edward Adolf Lejeune. Born Frankfurt(?), died Zurich, Switzerland. 1899.

There is no doubt that he was “in cotton.” Manchester’s damp climate suited the manufacturing of cotton. In fact, Manchester was the centre of the cotton trade.

It’s probable that he was born in Frankfurt, for, at the end of the 18th Century a popular physician Dr Francois Adam Lejeune lived in Frankfurt. This Dr Lejeune was determined that his two sons Edward and Gustav should have the best education Europe could offer. So, he searched in France, Germany and Switzerland. On his travels he learned that a man called Pestalozzi had a school at Zurich. He heard that some fashionable folk felt that the school was too rough and simple, put too little emphasis on social manners. Dr Lejeune visited Zurich so he could discover more about the school. From a distance he watched boys and some of the masters playing a kind of football in a field. He felt they were healthy, were energetic, happy looking boys and there seemed to be an easy informality about the way they welcomed any teachers who appeared. In fact, after having gone to the school itself, met Pestalozzi, and joined in a school meal where he found simple but healthy food, and the easy atmosphere so much to his liking, he sent his sons, Gustav and Edward, not yet in their teens, from Frankfurt to Zurich at a time when groups of soldiers from the Napoleonic wars were roaming across Europe.

My mother told me the story of Gustav and Edward. She was reading and translating from a thin green-covered book written in German by a Lina Lejeune. Mother mentioned too that Dr Francois Adam Lejeune and Pestalozzi had corresponded with one another, and that part of that correspondence was in a Pestalozzi museum in Zurich (see Appendix D).

It’s interesting to me that E. A. Lejeune, having fathered the four girls Franziska, Marion, Juliet and Helena, called his first son Gustav Alick, the second Edward Russell, and the third Frances Arnold whose initials F.A.L. were also those of Dr Francois Adam Lejeune.

There is no Edward among the Canadian descendants of E.A. Lejeune. Edward Russell, who emigrated to Australia, married Rachel Percy. They had four children – Josceline, Aynis, Patty and David. Josceline, writing for Christmas 1988 put her new address as 7 Wilson Street, Claremont, W.A. 6010. Widowed, she is Josceline Thom.

At Thousand Oaks, in California, there is an Edward Lejeune, son of Gordon Lejeune. This slim boy in T-shirt and jeans lives in a world that would startle Edward Adolf Lejeune. And yet, to me, there is a slight facial resemblance between this 1988 Edward and a portrait of his great-great-grandfather as a small fair-haired, blue-eyed boy wearing a green velveteen or corduroy jacket with a big, floppy light-coloured collar. The picture’s frame was narrow and golden, the surround was cream-coloured, and the portrait round not oval. A photograph of that photo should be in the Family Photograph box that Derek took back to Kamloops to file and “sort.” Max took the photograph of the picture, so it will be clearly marked and identified on the back.

Victoria (1921 – 1924)

The return to Victoria in 1921 was a let down and I think I must have been in a pre-adolescent haze. But I remember my bicycle, my beautiful dove-grey bicycle with a back-pedalling brake. It was only an ordinary push bike – no extra speeds. Few people had even a three speed. The idea of a ten speed was quite unknown to me.

The beauty of my bicycle was destroyed by my father who said that, if the chain snapped or came loose, I’d be without a brake and might have a fatal accident.

His solution was a rod going up the stem of the handle bars. It connected to a cable extending to the right handgrip. If I pressed a shiny lever that stuck up like a sore thumb from the bike’s original handgrip, the rod would activate the brake now attached to the front wheel’s rim.

My father was pleased. I was not. The new brake system was hideous. My beautiful bicycle was ruined. I was heart broken. It was quite simply the end of my world.

From 1921 – 24 I remember how we had a relief collection for the Japanese children whose homes had been destroyed in the Tokyo earthquake of September 1923. It was sad, of course, about all those homeless children, but they were so far away that they ranked about equal with “Eat your crusts and think of the starving children in India.”

After the Withington School, Victoria’s Norfolk House seemed small. As I remember it in 1922 it had two classrooms. One upstairs and one downstairs in a solid well built home on a quiet street. I remember it chiefly as where I first glimpsed etymology, as part of Miss Atkins teaching us Latin. I hated Latin grammar and the memorizing of conjugations and declensions. But when Miss Atkins talked of Rome, of the Holy Roman Empire’s spread, of monks copying medieval manuscripts written in Latin, the drudgery of grammar seemed less hateful. It was exciting to learn that language is forever changing, that words travel from one language to another, and that many words come down to us through the centuries.

I’ve forgotten most of the Latin I learned at school and university. But I do remember clearly that my first excited look at language was at Norfolk House School and was thanks to Miss Atkins’ teaching.

Perhaps my excitement was partly inherited from my maternal grandmother’s background, of a long line of preachers and teachers. Perhaps it partly stemmed from the “hunger of youth,” an expression that my mother used in her article Manchester Memories that appeared in the July – August, 1945, issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

It happened that Mother had heard her grandfather Dr Alexander MacLaren (a Baptist minister so famous that people travelled to Manchester to hear his sermons) mention in his sermon The Story of an African Farm and its “dreary creed.”

In The Horn Book mother wrote, ” The moment we arrived home I went to the dining-room bookcase in which were kept the grown-up books that we were not allowed to read, and, curled up on the floor between the bookcase and a large armchair, all ready to slip the book back if anyone should come, I started posthaste on Olive Schreiner’s story. The philosophy was beyond my comprehension, of course, but I was gripped by the power of the book, and there was a completely new atmosphere in it that I absorbed with the hunger of youth.”

Manchester Memories was the only article that Mother ever wrote and it was done entirely for the sake of her children and grandchildren [Editor’s Note: see Appendix A for a complete text].

Alexander Maclaren

Grannie Lejeune’s father was Alexander Maclaren (1826-1910), born in Glasgow on February 11, 1826, the youngest child of David and Mary (née Wingate) Maclaren and one of six children. His father, David Maclaren, was a businessman.

Educated in Glasgow and London, Alexander Maclaren became one of the most famous preachers of the nineteenth century. He began his career in Portland Chapel, Southampton in 1846, and, in 1858, moved to Union Chapel, Manchester where he stayed until 1903. On March 27, 1856 he married his cousin, Marion (who died on December 21, 1884). He died on May 5, 1910.

Alexander Maclaren’s preaching was so vital, so powerful, and so fresh that Union Chapel, which seated fifteen hundred, would often be packed with over two thousand who had come to hear him.

Many details of his life and sermons can be found in Albert H. Currier’s Nine Great Preachers, published by The Pilgrim Press in 1912. Included in the book are such other famous preachers as Bernard of Clairvaux, John Bunyan, and Henry Ward Beecher. In its bibliography are to be found the following citations:

Miss E.T. Maclaren The Life of Alexander Maclaren Hodder & Stoughton London, 1911

Sermons Preached in Manchester 3 vols MacMillan & Co.

The first book is out of print, but a copy is available from the University of Toronto.

After Stephen died, in 1974, I corresponded for a brief spell with Tony Thompson who wrote under the name of Anthony Lejeune. One night, to my surprise, switching TV channels I caught William J. Buckley Jr interviewing Bernard Levine and Anthony Lejeune. I watched with great interest. Tony was balding in exactly the same pattern as his father Roffe Thompson. But suddenly there was a fleeting facial expression that reminded me of the picture of Alexander Maclaren holding a very long thin-stemmed clay pipe.

England and the Continent (1924 – 1931)

In early 1924 we were once more packing for a trip to Europe as I was to be sent to boarding school in Sussex [The Downs School, Sutton Road, Seaford, Sussex]. My mother chose the school as she and the school’s head-mistress [Miss Lucretia Cameron] had met when both were teaching at a school in Southwold in 1901. Also my cousin Margaret attended this school at Seaford in Sussex, and was happy there.

So Mother, Stephen and I went to England. My father did not come with us. I rather think that, unlike Mother, he didn’t consider an English education was so much better than a Canadian. I can recall him seeing us off in Vancouver and looking sad as we went towards the train.

When Caroline moved to London, Grannie Lejeune moved there too. 8 Burlington Road, Manchester became 19 St Loo Mansions, Chelsea, where Mother, Stephen and I stayed, and where Russell and Rachel and Josceline were in 1924 – the first year of the Wembley exhibition.

The Wembley Exhibition was in 1924. I went to it fairly often as Roffe, the man my Aunt Caroline would marry, lived at Ealing and was delighted to have a young relative he could treat to a day at the exhibition. We went often, eating strange foods, wondering at the exhibits and taking in the amusement side of the exhibition. The Giant Racer scared me but it was so thrilling that we always had a turn on that. Caroline refused to go on a thing called Over the Waves. I went. The trip started with a walk down a dark passage. Suddenly, without warning, the floor gave way and I was dropped on to a heaving, rolling sort of canvas. It carried me along, helpless, and the sound of laughter grew louder all the while. Then, again without warning, the galloping canvas slid me safely to a stationary floor. The space there was full of people who’d gone “over the waves” on the trips before ours. They’d stayed to watch. We watched the next trip, too. The women tossing helplessly – their skirts tossing with them, and thus displaying all kinds of underwear, while some watchers hoped for a case of no underwear at all. I understood the laughter now and Caroline’s reluctance.

The exhibition in 1924 was so popular that it was repeated in 1925 although I didn’t go. The second year had fewer exhibits from the dominions and colonies and the entertainment side was enlarged and emphasized.

Somehow we fitted in some weeks at a village called Steyning [ed. note: Steyning is in West Sussex, 5 miles northwest of Shoreham-by-Sea which is between Worthing and Brighton. Steyning is described in the AA Book of British Villages, Drive Publications, 1980 and in the AA Illustrated Guide to Britain, Drive Publications, 1971.] Grannie, realizing that Marion and two children were in England, that Russell, Rachel and their eldest child Josceline (born September 1916) were also in London, and that Arnold and Gladys with their two children were leaving shortly for California, rented a house in Steyning. It was really a small boarding school so it was vacant during the summer and there were plenty of beds and bedrooms. “So the little cousins can get to know one another.” The little cousins didn’t care for each other as I remember. Especially after the incident of Joscie and the grapes. Grannie as a great treat had bought a large bunch of grapes. When a child was offered the bunch of grapes, he or she was meant to break off a stem with about 5 grapes on it. Joscie took the whole bunch, the way she was used to in Australia. (In the 1970’s when Josceline visited Victoria we laughed about this.)

I was the eldest of the cousins as Stephen, Diana and Josceline were all born in the summer of 1916, and Michael was younger.

We went for enormous walks on the Downs – to Cissbury Ring, to Chanctonbury Ring with the lovely rustle of leaves to be heard from its beech trees. I remember Russell scooping up a handful of water from a dew pond.

Later that summer, I was at Grannie’s Chelsea apartment when Russell and Rachel were there too. It was near the end of their stay I think. They’d been shopping madly one morning as they were going that afternoon to a garden party at Buckingham Palace. They were both very good looking and wore their clothes with style. They went in a taxi, Russell with a top hat, I think, and Rachel with a lovely garden-party dress and becoming hat. After the rush and excitement of their dressing and departure Grannie and I stood at their bedroom door and looked at box after box and the masses of tissue paper scattered around, wondering how such finery could emerge from such a muddle.

Boarding School

The summer of 1924 was not all Wembley, as we had to get my clothes for boarding school which started its autumn term about September 21 and not just after Labour Day (the Summer term lasted until the end of July so the academic year was about the same length as in Canada).

The school list of required clothes seemed very firm and official.

I’d been excited when I first read it – 2 coats and skirts – a navy one for winter and a white for summer and all those tussore shirts for summer. The white shirts were to go with the suits and tussore were summer wear under tunics, the red pullovers were winter wear under a tunic, 6 pairs of long black woollen stockings, black woollen tights and white cotton linings to wear under the tights, black felt hat for winter and white straw for summer, 2 pairs of black brogues, tidy slippers, bedroom slippers – top coat – mackintosh.

I was bored before we’d bought them all. Mother was worried about money and it was costing far more than she’d realized. She couldn’t see the point of all those vests. Roffe noted that much of the clothing was to be obtained from a firm Samuel Bros (or Samuel & Son). Old Samuel must be making a pretty penny, he said.

By September, I was thoroughly sick of counting the garments for school and seeing that each was properly marked. Cash name tapes – boxes of them it seemed. Years later in Victoria I met Gwen who’d married into the Cash family.

Then the final day came. In navy coat and skirt with black velour hat and trunk and first-night-case I was taken to Victoria Station to catch the 5.20 p.m. Victoria Station, serving mainly the southern counties, was an experience at the start of term. Many schools, many different uniforms. Not all on the 5.20 p.m. Not all the same sex. But all the same kind.

I spent five years at boarding school. They certainly left their mark on me. Ten years after I left school, I still had the occasional nightmare about the beginning of term and catching the 5.20 p.m. It was a good school of its kind – not as big as Roedean, less classy than Battle Abbey. But it was so ruthlessly athletic, so plastered with slogans about team spirit, hard work, self control. Recalling it now, I’m certain that there were only Anglicans there. I was the only girl in the school who’d never been christened. The snag was: no christening, so I couldn’t be confirmed; not confirmed, I could not go to Early Service at the Parish Church. Even when I was in the 6th form and a prefect, I still was obliged to go to Matins with the Juniors. A crocodile of all those chattering little creatures from the fourth form, in our school uniforms and wearing black suede gloves in winter. And standing, tall and gawky, while we all sang about “the rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate, and something, something, God ordered their estate” [ed. note from the unabridged version of ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful.’] No wonder I’ve never been a church-goer since!

The school slogans and mottoes were all in Latin. The school motto was Potens Mei quid non Possum i.e. Master of Myself what may I not achieve? Among the form mottoes were Per Aspera ad Astra, and Nihil sine Labore. The three “houses” were School, Tower and Bydown. I was in School House so my house motto was Play up and play the game. But in spite of these brave mottoes our winter greeting to one another was “Have your chilblains broken yet?”

Strengthening my character with mottoes like these for five solid years! When the time came to leave school for good, many of the girls cried. I do know that this school made me hate regimentation, compulsory religion and Birds Custard, especially when it was used to top off what we called Resurrection Pudding. Even a pudding had a religious name!

Life’s so full of surprises. Early in 1972 when I was dismantling my father’s apartment and checking the vast quantity of papers he’d amassed, I found a packet of letters I’d written home during my first year at Seaford. In them, there was no whining, no hint of unhappiness, and no mention of the horror of never being alone. For I found this herd living the greatest trial of all. Every minute of the day was organized. Even at night the dormitory was full of sounds of others. The only escape was in the winter evenings during the half hour between the end of prep and bedtime. Then I sometimes sneaked down to the cloakroom, took the rubbers I now called galoshes out of my numbered pigeon hole, and, stealthily crossing the road between School House and the huge playing field, began to run, run, run around the field in the darkness. Often it was cold and windy, but just running, wild and alone, was a help.

Judging by my letters home I was already brainwashed and an accomplished hypocrite. I destroyed all those letters after I’d read them in 1972 — the pages of thick white paper, and each stamped with the school shield and its familiar motto — so I have no actual letter to quote. But the fabricated one that follows is typical of most of them:

“Darling Mummy & Daddy,

We had a ripping game of lacrosse today. You should have seen Smithy run. She’s the fastest in the school, and this year she’s head of our house. Today, after games, she let me carry all her books up to the prefect’s rooms. Wasn’t it topping of her? She wants me to play my best for the honour of the house. And I shall jolly well try.”

[1988 comment: Where did I put my ulp-bucket?]

* * *

Possibly the pleasantest part of my time at Seaford was the long walks we went on Sunday afternoons. I grew to enjoy the Sussex Downs that had seemed so bleak and bare when I saw them first.

The arrangement for walks was safe and simple.

On the school notice board the listed walks showed which prefect or senior girl was taking the walk, and the destination. We signed under the walk we wanted to go on. Some leaders and some destinations were more popular than others. There were usually 6 – 8 in each walk, and walks would be about 8 – 10 miles. Our black brogues would get covered with white chalk. But Rupert, the boot boy, cleaned them and cleaned them well. I’m sure none of us ever thanked him. To me, now, such lack of thanks seems intolerable.

One of the favourite walks was to walk to the top of Seaford Head, along the top for a mile or so to a rise from which we could see the Seven Sisters marching firmly towards Beachy Head, then down to the Cuckmere, along the Cuckmere Valley to Alfriston. From Alfriston we went up steeply past the White Horse of Hindover where the short cropped turf had been removed to show the outline of the horse. (The Long Man of Wilmington was too far for us to walk. But relatives visiting by car on a designated date might take us there so we could see the Long Man looking towards the shires.) From the top of Hindover it was an easy downgrade to school and Sunday tea with the special treat of butter and jam, instead of the plain weekday either/or.

* * *

Our morals were well protected at school. The newspaper we were allowed to see in the last half hour of the day was the Times. One copy was put on a table in the “drawing room” which, instead of desks and wooden chairs, had two sofas and several arm-chairs all with cretonne loose covers. However, if the Times happened to contain an item that might tarnish our purity, we had to re-read the previous day’s issue.

Any mention of a divorce case was considered poor taste. Alan Patrick Herbert had joined the staff of Punch in 1924. He wrote as A.P.H. But it was not until 1937 that he and other M.Ps managed to modify England’s outdated divorce laws by securing passage of the Matrimonial Causes Bill (Holy Deadlock is the book by which he is best remembered.)

At the start of each term our private books which we had brought to school were scrutinized by the head mistress, Miss Lucretia M. Cameron. Approved authors were Anthony Hope, Baroness Orczy, Rudolf Sabatini. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes was acceptable — Edgar Wallace and Sax Rohmer were rather borderline. I never took any books to school as I had none of my own in Europe. At school the Library had enough for the hour of Reference Reading as they called it on Sunday evenings. My mother’s generation had had Sunday reading. Reference Reading simply meant reading nonfiction. If I stayed with Roffe and Caroline during a vacation, their house at Pinner Hall was full of books.

* * *

At the start of most terms, on the night before the dreadful day of catching the 5.20 p.m. from Victoria Station, I was taken to the theatre. So, in the Seaford years, I saw Rose Marie at Drury Lane, and The Desert Song. No No Nanette and The Constant Nymph. were at lesser theatres. Aunt Isabel much preferred musical plays, but she unselfishly treated me to The Barretts of Wimpole St. We watched the authoritarian Mr Barrett riding herd over his daughters, including Elizabeth who, a life-long invalid, lay on a sofa with her lower limbs discreetly covered by a shawl. Papa B. discouraged or forbade all potential suitors. Yet, after great tension and suspense, the handsome Robert Browning stood by the doorway and just inside Elizabeth’s room. He stood there, handsome, talented, the answer to a maiden’s prayer. Elizabeth didn’t wait to pray. He held out his arms and, joyfully, she ran into them on legs that had lain limp on the sofa for years. He clasped her in his arms. It was so beautiful and romantic that I was utterly thrilled. But a little whiffling sound beside me made me look down. Aunt Isabel was breathing rhythmically as she sat there, sound asleep.

The most carefree 5.20 p.m. departure I ever had was when Roffe took me to lunch in Soho. He was editor of John Bull at the time as the former editor Horatio Bottomley had ended up in gaol after a financial scandal. Roffe gave me a very good lunch at one of his favourite restaurants. Plenty of good food, plenty of wine, perhaps a bit too much as I was feeling fairly irresponsible as I hurried through the station to the platform for the 5.20 p.m. to Seaford.

There they all were — navy blue suits — school hatband with its crest — the school tie. Each girl had her “first night” case. Tuck boxes, neatly labelled, went into the luggage van with the trunks. We wouldn’t see them till next day in the “dorm.” And I was nearly late. I, the head of the House and the head of the School.

Potens mei quid non possum?

Thanks to Roffe, I didn’t give a damn!

* * *

I became Head of the House and Head of the School because I was competent, reliable, and able to address the entire shcool with ease. Also I reminded Miss Cameron of her youth, I think, when she and Mother taught at Southwold and they used secretly to smoke cigarettes behind one of the outbuildings. Also she was fond of me – I’d argued that she was wrong in not letting me go out with Maud Gordon on a visiting weekend. All because Maud’s father had with him the woman who was the cause of the recent Gordon divorce. Also when Roffe, to be annoying I think, had given me a new portable gramophone and a selection of current dance hits, Miss Cameron sent for me, furious at the noise. What had I got, and why? I simply, on impulse, gave her a hug and kiss and said I was just trying to give them a good time on my birthday, because the school had a good time on her birthday. She melted at once.

* * *

On Grannie’s bureau desk was a bowl of reddish wood that the Australian relatives had given her. Beside the bowl was a tall copper vase of which I have a tiny replica.

When Grannie died all but one of the bureau drawers were empty. In the top left hand drawer she had put her will, the necessary information for quick settlement of her affairs. She died of pneumonia in April 1936. My mother was staying at Grannie’s house Fallowfield. Her letter to Max is short:

“Mother died this morning after a very hard fight. She was pretty bad all yesterday, but was able to recognize all of us. At about 10 p.m. she began to get very bad, and at 4 a.m. the nurse told me to send across for Cis, Juliet, Alick and Caroline who were at Lane End. She sent for the doctor, too. At the end he gave her a little bit of morphia to help the pain and she died very quietly. It seems impossible that it’s only been two days and a bit since I came.”

They did as Grannie had wanted – Cremation at Golders Green, ashes scattered not kept. And the family gave Christmas Roses to the Garden of Remembrance. Dear Grannie, who was on Galiano Island when I was born in 1910. Dear Grannie, who when her own father died earlier in 1910, wrote that she was proud he’d given “the honour of his name to that great new social reform – cremation.”

In 1924 Grannie had been in Chelsea at 19 St Loo Mansions and Roffe and Caroline had been at Ealing. The move to Pinner Hall in Middlesex must have been in 1925. Grannie called her house Fallowfield and Roffe and Caroline’s was Lane End. Roffe’s surname was Thompson but professionally Caroline always used Lejeune. Mrs Thompson would come to see them on a short visit. Like Gracie Fields she’d been a Lancashire Mill girl. She couldn’t sing like Gracie but when she wanted to help the family finances she taught herself to write. I never read any of her books but I think they were romances that used her knowledge of mills and mill girls — their home lives, their dreams. I’d be interested to read some of them now but it’s doubtful they still exist. Good Lancashire grit.

Roffe and Caroline had only one child, Edward Anthony. He grew up to write too, as Anthony Lejeune. Patrick Lejeune who lives in Pasadena knew Tony and has had him staying there. After Tony’s birth in 1930 Caroline began writing in the Observer. Whenever I was staying at Pinner, I naturally heard a great deal about films and went to see as many as I could as Caroline passed on her spare press tickets to me.

These Sunday advance film showings attracted a number of fragile affected young men whom I’d only met in Patience or Buncombe’s Bride that I had in my collection of Gilbert and Sullivan gramophone records.

In Act 1, Reginald Buncombe (a fleshy poet) had seen the splendidly uniformed officers of the dragoon guards rejected by the twenty love-sick maidens who had preferred melancholic aesthetic men. In Buncombe’s opinion “Though the Philistines may jostle, you’ll rank as an apostle in the high aesthetic band, if you walk down Piccadilly with a poppy or a lily in your medieval hand…”

The free run of all the books at Lane End was a glorious time for me. No restraint at all. Roffe, who became editor of John Bull after the embezzlement scandal that put Horatio Bottomley in prison, had political books, books about journalism, celebrated trials, and plenty of good detective stories. Caroline was apolitical and her books were more literary. Her background, upbringing, University years had made English literature a part of her. In fact, the title off her second book Chestnuts in Her Lap comes from Macbeth, Act 1, Scene 3, where the First Witch, chatting to her pals on the blasted heath, says

“A sailor’s wife had chestnuts in her lap,

And munched, and munched, and munched.”

In the 8 Burlington Road days of our Manchester visit I’d been exposed to Caroline’s collection of Andrew Lang’s Colour Books. Among her books I’d also found those by George Macdonald, whom Grannie said was some kind of cousin on the Maclaren side. Caroline had At the Back of the North Wind (1871), The Princess and the Goblin(1872), The Princess and Curdie(1882).

In the Blenkinsop Valley days, I treated myself to A Critical History of Children’s Books, published by MacMillan Company, New York in 1953. It is one of my treasures. I’m really proud that I know so many of the books listed in the 15 page index at the end. The Introduction is by Dr Henry Sleele Commager, the Foreword by Cornelia Meigs who wrote the first of the four parts of this book which I consider should be in every college library even if it does not yet offer a course on children’s books. For this book, as it states clearly, is a survey of children’s books in English from the earliest time to the present. Part 3 is written by Anne T. Eaton, so well known in the world of children’s books in America. In her chapter on the gift of pure nonsense and imagination she rates George Macdonald as the greatest of Lewis Carroll’s contemporaries. Indeed she writes that Carroll and Macdonald were friends. Carroll told stories to the Macdonald children, and Macdonald urged the publication of Alice in Wonderland. Macdonald was a novelist, poet and clergyman. He studied for the Ministry, but resigned after holding a pastorate for three years. He was too visionary and not dogmatic enough for his congregation according to Anne T. Eaton.

Pinehurst and Oaklands

Pinehurst, home of my paternal Uncle Peter, was an important and happy part of my Seaford years. For, when I was left at boarding school and both my parents were in Canada, my official guardians were Uncle Peter and his wife Isabel.

Pinehurst was next door to my paternal grandfather’s house Oaklands. No fence divided the two properties — but we all knew the invisible line was the long straight sandy path past the mulberry tree.

In World War I Peter’s family had fled over the frontier to neutral Holland. From there they went to England. Because Enke was a German name and anti-German feeling was very high in England, Peter Hermann Enke changed his name to Henry Peter Armstrong. This was largely for the sake of his children, Godfrey (born 1905) and Margaret (1907) and usually called Margy.

Before they fled to Holland, they hid the silverware in the hollow terrace that was part of the house front. Otherwise, from what my parents told me, everything was simply left — clothes on their hangers, family photographs on the mantelpiece, and so on.

My grandfather stayed at Oaklands and so did his twin daughters Paula and Ady. The twins had been born in Manchester, England in August 1877.

In my teens I was not interested in all the details but I remember remarks about Ady going over to Pinehurst on routine inspection visits. German officers were quartered there and things should be run properly. I doubt she actually kept the linen cupboard key and issued linen as needed. But Ady slipped up on the brass stair rods. Towards the end of the war the Germans were getting short of brass and the stair rods, I think, were the only objects which disappeared. Ironically, the British, knowing that the German officers were quartered in a big house in that area, mistook their houses (and missed them!) When we were at Oaklands in 1919 the windows, shattered by the bomb that landed on the front lawn, were still without glass.

During the years I “belonged” to Pinehurst I had lovely clothes. Our shopping was mostly done in Ghent. Approaching Ghent we took the route that would let us see the three towers St Bavon, St Nicholas and the Belfry with the golden dragon atop its spire. Monsieur Verstraete was the tailor who made my brown coat, beautifully cut and finished, that had a becoming fox fur collar. I was proud of that coat but when I showed it off to Roffe in England he muttered that “it smelled of money.” Money-smelly or not, it was a stylish, flattering coat. Aunt Isabel went to Odette’s for lingerie. I had some beautiful camiknickers, with my initials expertly embroidered by hand. The silk was so slinky. About this time I had a black evening dress, of taffeta, I think. It was stiff and the hem dipped in a graceful curve at the back. It was simple, youthful and worn with a single strand of small pearls round my neck. Waists were low, skirts were short, and my two favourite summer dresses were of striped silk. Another favourite garment was an accordion pleated skirt with a pretty, silky jersey top. That skirt spun out beautifully when one twirled. Tidy stockings were silk, ladders were repaired with a ratchet crochet hook. No Nylons existed.

Pinehurst, too, was the place of good cars. Both Peter and Godfrey were very interested in them. Godfrey started with motor bikes, and later there were his cars. I remember the grey Rolls being shipped over from England. This car was later nicknamed the Super Standard. He was a good driver – and there was one lovely day when there were four of us out in the car, the hood was down and we drove very fast along part of the coast highway called the Route Royale.

Clothes were to the fore in February, 1928, as Godfrey married Denise Piron, the youngest and prettiest of the four sisters who lived with their widowed mother at Ostend. The wedding was in London. Margy and I were among the six bridesmaids. Our dresses were blue georgette over a pink satin slip. In 1988, I sent a night letter of Congratulation on their Diamond Wedding Anniversary. I timed it so that it would be delivered by the first post on Feb 2, the CNCP telegram service said. About the 5th of February the phone rang. A man’s voice, saying Ruth. It was a familiar voice. Godfrey saying the message had arrived safely — we talked briefly and the he said he’d put Denise on. From her I learned that he’d had a stroke in January so the Feb 2nd celebration was to be held later that month. Godfrey’s improvement continued as in June I had a letter from Denise (but signed by Godfrey). He wondered how long it would be before he could drive and wanted to know how soon after a cerebral aneurysm I was able to drive. He also wanted to know whether the Timmis Motor Co was still making model cars. I haven’t answered yet (July 15) as our cases were different. My epileptic fits, caused by brain damage meant that I must have two fit-free years before driving. I was born in 1910, Godfrey was born in 1906, so I would doubt that he could drive again.

I’m truly sorry about his illness. For he and Margy were like older brother and sister to me in the Pinehurst years.

The comfortable lifestyle at Pinehurst was largely because the H. Enke factory did well, very well, in the years right after World War I. Millions of European men, demobilized, needed civilian clothes. That included hats. The H. Enke factory bought rabbit skins, treated them, and turned them into fur felt for the hat trade. I’m glad that I had those years of good clothes, fine cars and solid comfort. I enjoyed them, but I’ve never hankered for them since as the experience is tucked away in my mind as useful knowledge that’s akin to inoculation.

Austria

I had a summer vacation in Austria during the time that Peter and Isabel were my guardians. The parents of “Tommy,” a girl who’d been sent to the school at Seaford to improve her English, were going to Austria that summer and wanted Tommy to bring a school friend with her. Tommy’s father, German and Jewish, had a chemical factory at Frankfurt am Main. Her mother was French, graceful, beautiful and charming. Tommy’s parents had rented Prince Hohenlohe’s villa in the village of Alt-Aussee as well as his chamois shooting in the nearby mountains.

Peter and Isabel prepared me for the trip. Nailed boots for the walk up to the shooting boxes in the mountains. Sturdy boots with rubber soles for walking in areas where the sound of nails striking rock might warn the chamois — a sort of green Harris tweed suit with plus fours instead of a skirt. I went by the Brussels — Frankfurt train. It was after midnight by the time we reached Tommy’s home which looked enormous in the headlights. Tommy had a whole wing of the house as a sort of apartment of her own. Bedroom, bathroom, guest room, sitting room and porch. In the morning we looked at the swimming pool and some polo ponies.

On the following day, Tommy, her mother and I set out for Austria in a sleek black immense car driven by the chauffeur Schneider. Our route was via Nuremberg, Munich, and over the frontier into Austria, where we were to stay for several days at Salzburg, so we could enjoy the Salzburg Festival which was one of Europe’s more important social events. I was too much the unsophisticated schoolgirl to enjoy the wealthy elegance of the people at the festival. Tommy blossomed and seemed a natural part of that expensive social scene. My highlight was Max Reinhardt’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I knew no German, but I’d recently had to study this play in detail as part of an important exam. To me, the exciting, surprising aspect of this production was that, in spite of not knowing German, I could somehow understand and appreciate each sentence. Now I could believe people who’d been to the Passion Play at Ober-Ammergau and noticed no language barrier at all.

After Salzburg we went to the village of Alt-Aussee. The villa was simple and charming. The cook who “went” with the villa made us unforgettable desserts involving small alpine strawberries.

The Prince and Princess Hohenlohe visited the villa one afternoon. Tommy and I, carefully coached by her mother, curtsied and kissed the hand of this gentle-faced woman in a simple summer dress. The Prince wore the shabbiest, oldest lederhosen in the village. In later years I’ve often wondered about that summer visit. Rich, industrial Jew renting shooting and villa from impoverished nobility? What were the true feelings on either side?

It was about a four hour walk up to the shooting box. Our party was Tommy’s parents (Tommy’s father had joined us for part of the summer), Tommy and I, a sturdy village girl who’d cook for us and for the game keepers, guides and gun carriers who walked up with us. We carried no packs. The time in the mountains was marvellous — the keen fresh air, the feeling that one could walk forever. Tommy’s parents each had a party. Her father liked to shoot. Her mother preferred photography. We both preferred going with her mother.

It was quite the grandest, most memorable holiday I was ever to have.

Not until later years, did I really understand Tommy’s whispered remark that her father was a Jew, but they never talked about it. I didn’t hear much about Hitler until 1933 when he rose to power. By then Mein Kampf was a best-seller. But much of the material that ultimately became Mein Kampf was written by Hitler in 1924, and some of it was published in 1925. It’s probable that Tommy’s parents, both well read and well informed, were aware of the political ferment and currents that preceded Hitler’s rise to power.

I lost track of Tommy and her family when I left the Seaford school, but I heard from somewhere that she’d married and was living in Sweden.

Oxford

I’ve mentioned the Seaford School several times: the school motto, song, and spirit, the walks, the compulsory religion. I’ve not written of the academic, scholastic side.

Perhaps this is because I didn’t learn for pleasure at Seaford. I was cramming for exams. Because I’d got very good marks in the Oxford and Cambridge School Certificate, my mother and Miss Cameron decided that I should try for University. By that they meant Oxford or Cambridge. Mother had gone to Cambridge, Miss Cameron to Oxford.

This meant serious study of required subjects and strict adherence to the official syllabus. In the 1920’s there were four colleges for women at Oxford — Somerville, Lady Margaret Hall, St Hilda’s and St Hughes. Their popularity and academic standards ranked in the same order. In the 1920’s the competitor was 10 girls for every vacancy. I tried all four and failed all four. So then I tried Newnham and Girton, Cambridge University’s two colleges for women. I earned an interview at Newnham where Mother had been a student. I failed Girton outright and Newnham after the interview. So a lesson I learned in that decade was how to fail and bounce up again.

“If at first you don’t succeed,

Try, try, and try again.”

So my next try was for the exams set by Oxford Home Students. O.H.S. had head-quarters and common room at No 1 Jowett Walk. Their students were full members of the University but, as no residence yet existed for them, they boarded at certain approved Oxford homes. I was at 26 Leckford Road with 3 other women students. Three of us were ordinary first year undergraduates; the fourth, Eileen Lloyd, was reading French and up at Oxford because she had won a scholarship. At some date after I left Oxford, O.H.S. acquired or built a residence, and are now a fifth college for women, St Anne’s.

Any student, man or woman, with less than an M.A. was considered a junior member of the University and was obliged to observe rules of conduct and discipline ordered by the Vice Chancellor. The rules and regulations were enforced by the Proctors (or, as the students called them “progs”) who were, in reality, university police. Because the university rules of that time were so different from those at a Canadian university of the 1980’s, it’s almost a shocker to read “MEMORANDUM ON THE CONDUCT AND DISCIPLINE OF JUNIOR MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY” as published by the university in autumn 1929:

1) No loitering in the streets, coffee-stalls or at the stage door of a theatre

2) No taking the chair at any open-air meeting of political character, without special leave from the Proctors

3) May only be present at those entertainments licensed by the Vice Chancellor

4) Undergraduates strictly forbidden to visit the bar of any hotel, restaurant or public-house

5) An undergraduate in residence is not permitted to drive a motor vehicle without a Proctorial licence, which will not be issued during the first three terms of residence.

Briefly, no car for first year students, academic dress i.e. cap and gown for women and gown for men had to be worn if out of college after 9 p.m. (this was to help the progs nab their victim). Scholars (those who’d won scholarships) wore long gowns and for a woman scholar that meant hem length. The gowns of ordinary students like myself were short and only reached the waist. Often these gowns were little more than a scrumpled rag or a scarf. Flying was not allowed without Proctorial permission and the written consent of parent or guardian. Hotels, restaurants, garages and teachers of dancing all needed university approval. No mixed parties — a laughable notion by the standards of the 1980’s. But a brother and sister could go to the cinema together!

We all bicycled to lectures and every hour, on the hour, the streets were filled by cyclists riding madly to the next lecture which might be at almost any college. First arrivals grabbed the seats nearest the fire.

I had gone up to Oxford to read English. The English school had two sides — literature and language (i.e. Anglo-Saxon, then Middle English) My knowledge of literature was considered disgracefully low. My skill at Anglo-Saxon (i.e. Old English) was considered good. I did not explain that because of holidays in Belgium, I’d picked up some words of Flemish. And as Flemish and Anglo-Saxon are vaguely connected since both come from the same Germanic branch, I’d simply managed some lucky guesses when I had to translate from the Anglo-Saxon Reader. Thus the academic advice was that I should emphasize and concentrate on the language side of English and do what I could with my skimpy literature. It seemed to me that such specialized knowledge would mean being shut up in an ivory tower for the rest of my days. I rebelled and said I wanted to see what life and normal emotions (and enthusiasms) were like. My tutor told me that every existing human emotion was described in English literature. I was rude and said vicarious wasn’t good enough. The O.H.S. principal said coldly that I was throwing away the best education in the world.

So in spite of the criticism, the years of cramming at Seaford, the floods of tears when I heard I’d failed yet another exam for Oxford, I left Oxford cheerfully. I’d met some unfamiliar types, acquired some useful knowledge of social attitudes. I am still convinced I only got up to Oxford on my General Knowledge paper (The Salzburg Festival production of a Midsummer Night’s Dream and natural history in the Gulf Islands — botany and birds chiefly — my enjoyment and varied interests, I think.) But I’m grateful to my tutor who helped me often to find exactly the right word for the shade of meaning I wanted my essay to express. I still remember with delight a series of lectures on how the newly translated Bible influenced the seventeenth century writers. It appears in the work of men as unlike as Milton and Bunyan.

Two small Oxford purchases are with me still. The bookends depicting the “dreaming spires of Oxford” are on my desk, and, on the mantelpiece, is a miniature chest of drawers in which I keep my supply of postage stamps [both now at Eagleridge].

Belgium, 1930

I crossed the Atlantic twice in 1930. Mother, Max and I were going to Victoria, B.C. for 6 weeks during which we’d dismantle 572 Island Road and ship most of its contents to Belgium via the Panama Canal.

In 1926, Hermann Enke had died in his Oaklands bedroom. Born in Barmen on February 5, 1847 and dying in February 1926, he was 79. Of his four children, Peter was 50 and living in Eecloo, Paula and Ady, born August 3, 1877, were 48½ and continued living at Oaklands until Hitler’s Blitzkrieg in May 1940.

Max may have come to Europe briefly in 1926 as he certainly came down to Seaford to see me in some year before 1929 [Ed. Note: Max crossed by steamship from Canada to England in June 1925 and returned to Canada in October 1925], and he definitely was in Victoria in 1925 and 1927 as he won the B.C. Chess championship in both those years (if any of his descendants plays chess, I gave the precise record of one of those games to the Provincial Archives in 1971. I thought that some future chess player might be interested to see what standard of play was championship class in the 1920’s. Ask at the Information desk in the reference rooms. Most of the Enke papers and photographs are in the manuscript file but the chess game may be in a different category.)

I don’t know when Max decided that if he was to run the factory, we must have a family home. For that we needed furniture; hence the 1930 trip to Victoria.

That trip re-directed my life. I’d been a child when I left in 1924. I was now at Oxford and beginning to realize that a scholarly life was not what suited me. Canada seemed so lovely and so free of the class distinctions I’d met in Seaford, Oxford, and Belgium. I’d rather live in Canada than Europe.