Report by Derek Chambers

Why is Manchester in the UK important within the Lejeune family?

Dr Alexander Maclaren, wife Marion, their one year old daughter Jane Louisa and her younger sister Mary moved to Manchester from Southhampton in 1858 so Dr Maclaren could take up the pastorate of the Union Baptist Chapel. It was in Manchester then that Louisa spent her childhood, married, birthed eight children and, for 63 years, until 1921, lived in its outskirts, in Fallowfield and Withington. Manchester was very much part of Louisa’s life, so it’s important to set the scene.

Manchester is in the Northwest of England.

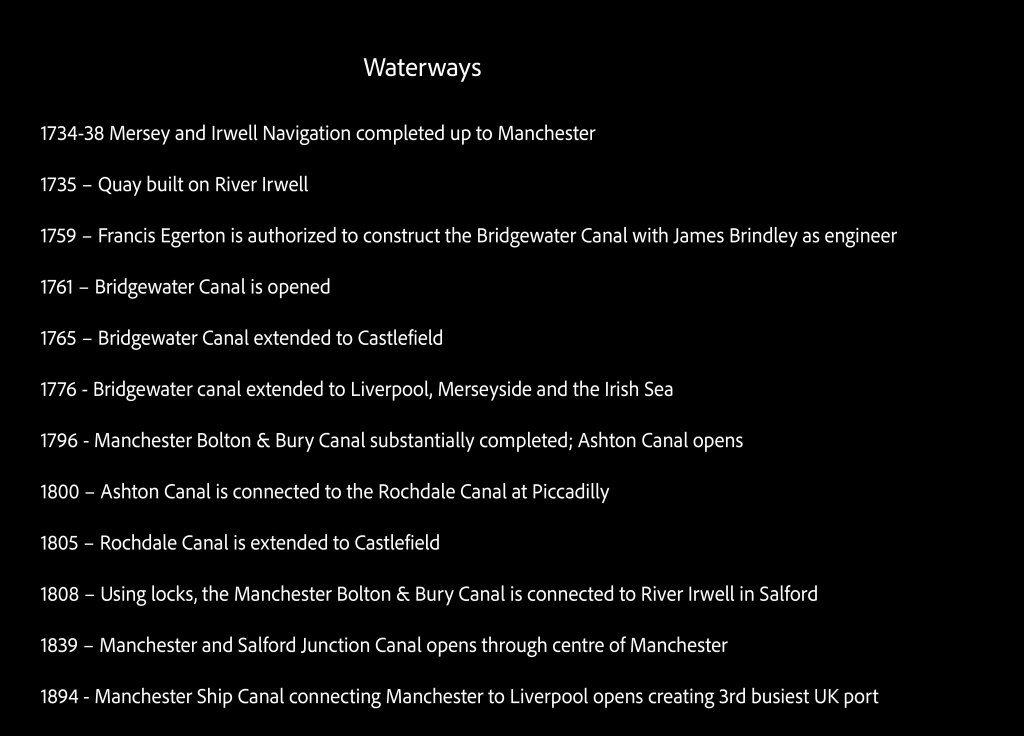

Its location has many advantages as we’ll see: rivers and streams, such as the Irk, Irwell and Medlock, the latter a tributary of the Mersey. These waterways were used for transportation, fishing and as sources of water power for water mills. Manchester is also close to Liverpool which has Irish Sea access for imports and exports.

Although the Romans established a fort there in 47 AD our story doesn’t begin until the 14th Century when Manchester became home to a community of Flemish weavers, who settled in the town to produce wool and linen. This helped to develop a tradition of cloth production in the region.

By the 16th century Manchester was a flourishing market borough important in the wool trade, exporting cloth to Europe via London. In 1542 it was described as “long time well inhabited, distinguished in its trade both in linens and woollens whereby the inhabitants have obtained riches and wealthy living and have employed many artificers.” Fustian weaving arrived in 1620 and silk weaving in 1637.

In 1717 Manchester’s population was 10,000; in 1832 it was 180,000. What drove the stunning increase?

The invention of the Spinning Jenny or Engine in 1764 marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and initiated the first fully mechanized textile production process. The many small valleys in the Pennine Hills to the north and east of Manchester, combined with the damp climate, proved ideal for the construction of water-powered mills which automated the spinning and weaving of cloth.

Beginning towards the end of the 18th century, the importation of cotton revolutionized the area’s textile industry. Raw cotton was imported through the port of Liverpool, then to Manchester via the Mersey and Irwell Navigation. Home based weavers undertook the basic processes – preparation of the raw material, carding or combing, spinning of the yarn, and some weaving of cloth.

Richard Arkwright is credited as the first to erect a cotton mill powered by steam in the city. Rapidly new cotton mills were built throughout Manchester itself and in the surrounding towns. To these must be added bleach works, textile print works, and the engineering workshops and foundries, all serving the cotton industry.

Manchester developed as the natural distribution centre for raw cotton and spun yarn, and a marketplace and distribution centre for the products of this growing textile industry.

Canals proved especially useful during this period. The Bridgewater Canal was completed in 1761, bringing coal by barge from Worsley, cutting the cost of coal in Manchester in half. It was followed by the other canals not just locally but all over England.

The coal required to fuel steam engines was transported to the mills from distance, along these canals, feeding the rapidly increasing demand. Raw cotton and wool, as well as finished products, were also carried along these water routes. The canals were lined with textile mills of several different types. Other factories, such as iron casting and machine manufacturing plants were also established in Manchester.

During the mid-19th century Manchester grew to become the centre of Lancashire’s cotton industry and for some years the world’s most important industrial centre. Cotton was imported from the British colonies and the southern US states, transported to Manchester from the nearby harbour at Liverpool. The industry experienced a boom following the invention of the steam engine and attracted large numbers of workers from the poor rural population. Cotton textile production in England rose from 1,300 tonnes in 1760 to 190,000 tonnes in 1860.

The Dark and Inhuman Side

The 18th and 19th century textile industry inventions triggered a revolution in the home based manual farmer-weaver industry. Countless family farmer-weaver enterprises could not compete, lost a substantial portion of the base of their living, and were forced into poverty. They had to become poorly paid labourers or move to work in the very mills that had overturned their lives.

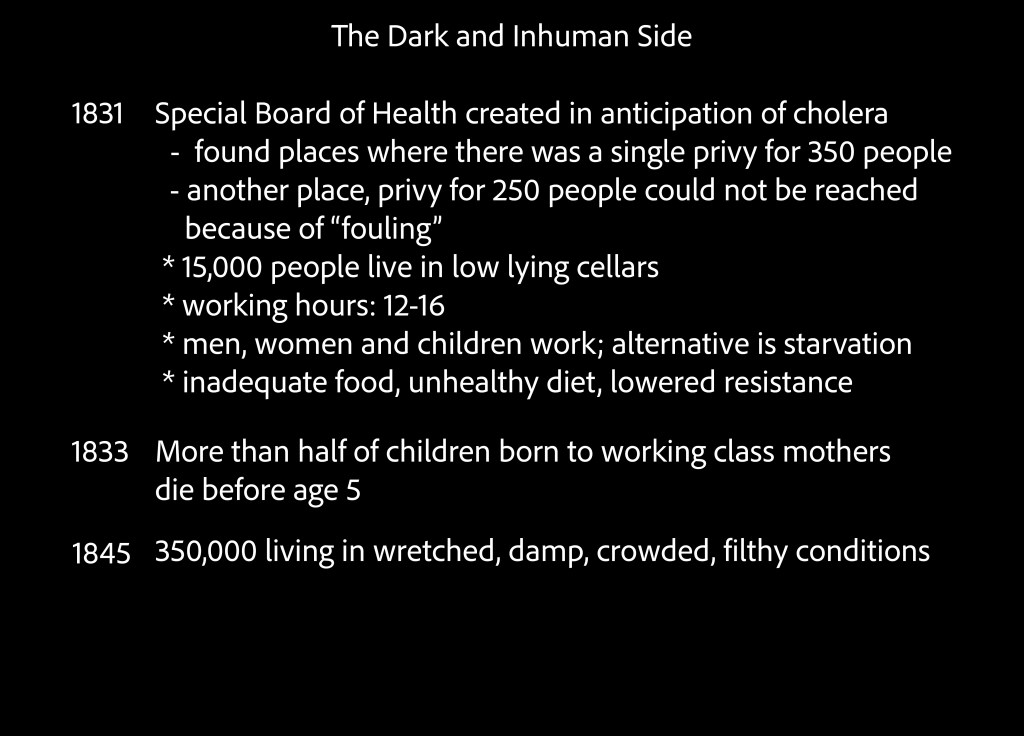

Manchester city centre became encircled by densely-packed inadequate working-class quarters, in which residents lived and worked under appalling hygiene conditions. The prominent use of coal for heat and energy in homes and factories polluted the atmosphere. Often children were forced to work; the alternative was family starvation. Illiteracy amongst both children and adults was widespread.

In 1832 James Kay, a doctor, published “The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester” which revealed the horror and degradation in which the workers existed and the toll it exacted on their families. For example, more than half of all children born to the working classes in Manchester died before their fifth birthday.

A French writer who visited Manchester in 1835, called it ‘this new Hades’ and added: ‘From this foul drain the greatest stream of human industry flows out to fertilize the whole world. From this filthy sewer pure gold flows.’

Population Growth and Immigration

Manchester became a magnet for many who wanted to learn and profit from the new way of doing things. This was particularly true for the emerging “commercial bourgeoisie” or Merchant Class in England and the Continent. Typically a trusted son or a clerk, earmarked by his talent for early promotion, was sent to Manchester to learn. Not unusually it happened that the fortunate student succeeded beyond expectations and Manchester replaced the home town as the centre of the family’s trading activities. Personal examples are my great grandfathers Herman Enke and Adam Eduard Lejeune.

Education

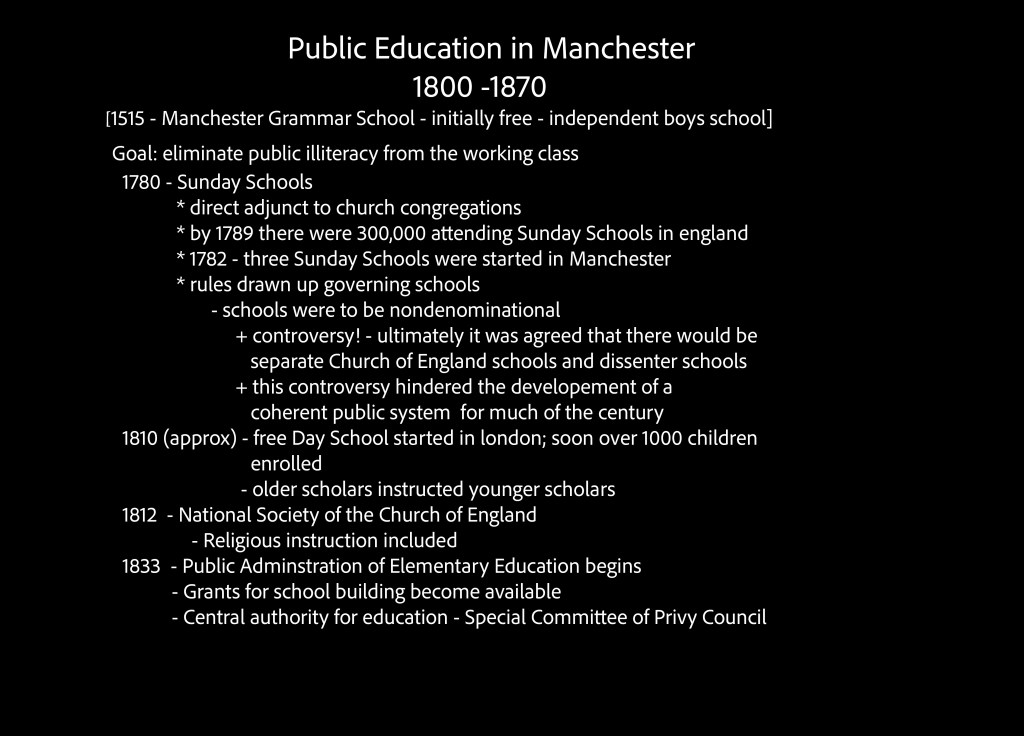

In the 18th Century illiteracy was widespread. Beginning around 1780 churches began to add Sunday Schools to their congregations until, in 1790 there were some 300,000 scholars attending Sunday Schools. Many congregations were assisted by private benefactors. Rules were drawn up to guide their governance; there was general agreement that Sunday Schools should be undenominational. Meanwhile, in London, a Day School for poor children was established and soon thereafter one in Manchester.

Meanwhile, nationally, in 1833 public administration of elementary education began and funds were provided as grants for school buildings. School districts were created in order to organize receipt of public funds and to report on their use. To test the efficacy of their use, inspection and control was introduced and almost immediately a disagreement arose as to the accuracy of reports from Manchester.

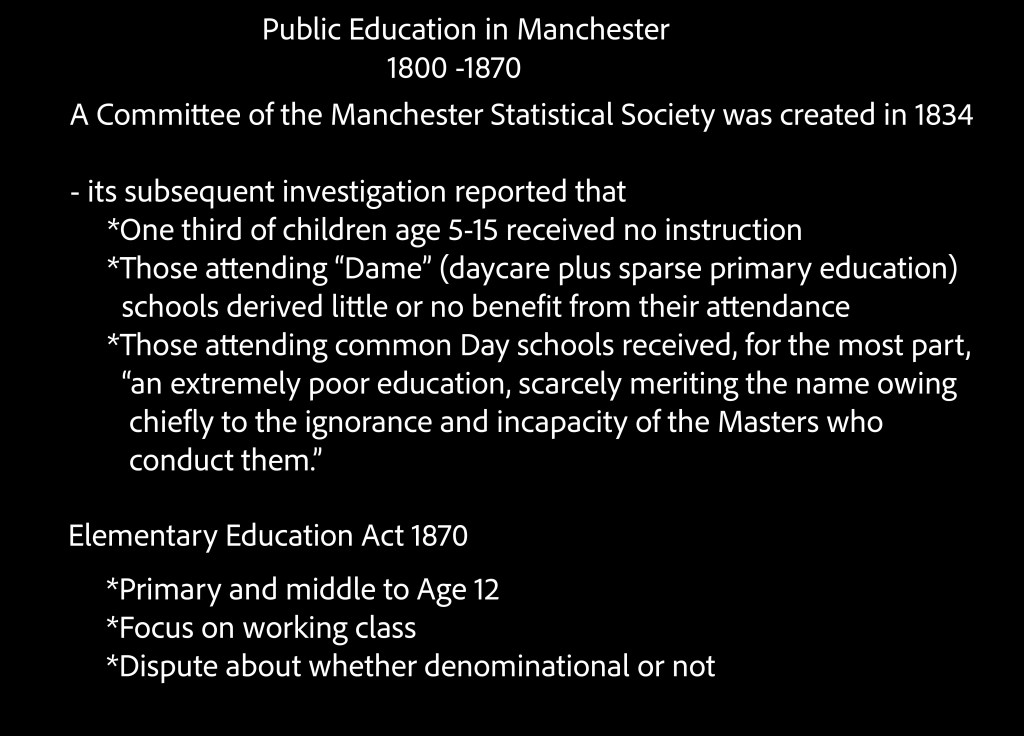

A Committee of the Manchester Statistical Society was created in 1834 and its subsequent investigation reported that

- one third of children age 5-15 received no instruction

- those attending “Dame” (daycare plus sparse primary education) schools derived little or no benefit from their attendance

- those attending common Day schools received, for the most part, “an extremely poor education, scarcely meriting the name owing chiefly to the ignorance and incapacity of the Masters who conduct them.”

Elementary Education Act 1870

- Primary and middle to Age 12

- Focus on working class

- Dispute about whether denominational or not

So that is a very broad brushed picture, incomplete because of time constraints, of the Manchester world into which Louisa Lejeune was born and grew up.